Pictured above: Gamejam pizza!

This post is a transcript of a talk I gave at BIMM University, Berlin. Thank you for inviting me! I had a lot of fun sharing :)

Links in this slide ~

tetrageddon.com

alienmelon.com

alienmelon.itch.io

mackerelmediafish.com

Games make impactful, unique, and complex storytelling possible.

I think we have only scratched the surface of what that means, because interactive digital art is such a huge possibility space.

It’s also important to look beyond games, and engage with other digital art, to really understand how broad a spectrum of experiences games are part of.

We are really only held back by our habit of how we look at something. Our conceptions and expectations are our only enemy.

Anything is possible when we create here. The biggest hurdle to making interesting impactful work is to think outside of commonly held beliefs or established standards.

Storytelling is one of those things. Games, and the broader space of digital art, is our collective fantasy. What we create pushes the boundaries of what that is.

I think that small game engines can help us realize all this unexplored potential.

In this talk post I hope to show how they helped me explore new and compelling ways to view interactive fiction, and maybe they can do the same for you!

Links in this slide…

Games are giant weird story machines!

Games Writing

Games are giant weird story machines.

They’re complicated structures. They’re often convoluted by their own complexity.

It depends on what you want from your game, and there’s a million ways to design one so that it’s a meaningful experience to people.

You will more often than not work against the system you created to be able to communicate a story, because a game’s story has to be designed around a system.

Games are this medley of mechanic, visuals, sound, and then the story that kind of ties it all together… sometimes more successfully than others.

Story is often stuck in this weird silly realm of afterthought while being incredibly important.

I know people will say that about every aspect of a game, but for me it’s the story.

A game’s story is the justification for a player to exist in a space, the way it informs atmosphere, and the resulting experience people get from it.

A game wouldn’t be the same without the context you give it through its fiction.

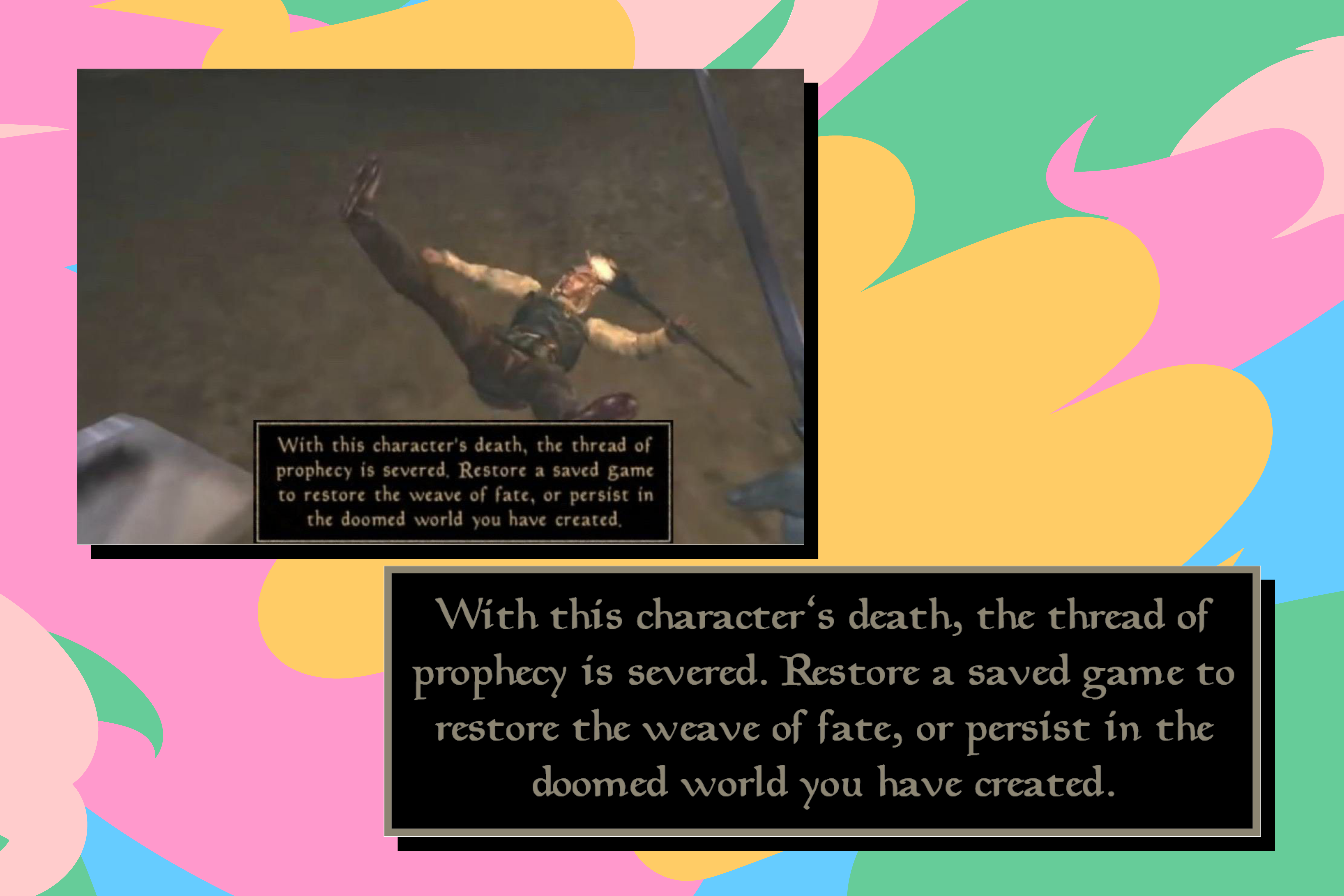

For example, one of my most favorite early experiences I had with video game story dissociation, that very much highlights the space video-game story is often stuck in, was when I was playing Morrowind.

This is a very old one…

You have this main quest line, and the game has characters that are vital to it. If you kill one of these characters before they fulfill their part in that quest you will get this notice saying:

“With this character’s death, the thread of prophecy is severed. Restore a saved game to restore the weave of fate, or persist in the doomed world you have created.”

Which I always found hilarious.

Like, to start, it’s quite a creative way to handle a warning dialogue to tell you “You broke my story.”

I also find it fascinating because you can keep playing this version of the game, indefinitely, with it being stuck in a broken limbo.

As a designer you can’t account for everything. Sometimes you just have to let players play on their own terms, even if it means playing in a limbo.

See how Red Dead Redemption 2 has an out of bounds that you can actually get to through a complicated way of breaking the game by exploiting a bug.

Red Dead Redemption 2’s out of bounds (see the above video) is this really fascinating video game void where everything is just broken and weird. Animals will spawn in a broken landscape and just kind of stare at you. Water doesn’t work right… If you explore it long enough you can glitch into future parts of the story (kind of warp). It’s an example that really fascinates me because, if you manage to get there, all the world building just kind of melts away and it feels like the game’s playable space is surrounded by an infinite backrooms type void.

All this very much captures the caveats of story-telling in games.

Games want to break.

Once the curtains get drawn because of a bug, and the system’s flaws show through, all that world building and story break with it.

This is especially true with the more epic (or complicated) you try to make your story, and the more you take control away from the player.

It’s also worth pointing out that games often don’t let you kill important characters, which (either way) breaks the immersion that they created with these exceptions.

So, as a designer, you have to find ways of structuring everything in a way that’s both compelling and also almost “invisible”.

For myself I found that metaphor, abstraction, and just “hinting” at what is happening, is better than being too heavy handed.

Otherwise, if a player notices that there’s a story, it’s likely to be the type of realization of “You broke the game by killing this character. Please reload…” because the immersion broke.

For example, Half Life (1 and 2) were viewed as revolutionary in their time because the story wasn’t treated as a cut-scene, but something the player could be part of… Characters talked, and the player could mess around in the room while they did.

Even so, immersion suffers all the time in games.

You can’t account for bugs in games… like the order that a player may experience your game, or even classic bugs like physics glitches…

I’ll show some that I collected, because all these in one place give you a good idea of what I mean when I say games are inherently weird…

They’re nightmarish, feverdreams, I don’t know why we try to make them imitate reality.

Click here for my saved collection of Assassin’s Creed 3 Bugs!

It’s really funny to look at accumulated examples like these, and then look at how popular media views games when they parody video games. They’re always weird, silly, almost comedic incohesive things.

The amount of suspension of disbelief it takes to feel immersed in a video game story and world is often a big ask.

So, in the end, games are quirky weird story machines. We should embrace that!

I think the suspension of disbelief happens when we don’t fully embrace the flaws of the medium and act like they’re something that they’re not.

Games are not movie, or theater. Games are a form of digital art. Their glitchy bugy-ness is just as inherent to them, as when they actually work.

This is why we shouldn’t have to follow in the footsteps of imitating existing media, or how things have been traditionally done.

Traditionally, most storytelling in games happens surrounding a mechanic, and the story is a reward for progress. This is pretty much the default. You can think of any game, and it will typically handle a story like this…

Two that I think are compelling examples for how story is seamlessly part of the interaction, and the interaction enforces the story, are Celeste and Yume Nikki.

I find both of these inspiring because neither are very heavy handed. They’re not overly ambitious, or pushy about how you experience them. The player is given space to understand the story, while the way you play the game reinforces it.

Celeste is this wonderful metaphor about climbing a mountain, where the character has to kind of face herself in that journey. It’s not very explicit about what is happening, so there’s a lot of space for the player to read themselves into it.

There’s lots of metaphor in terms of how you interact with the environments, certain elements that are harmful or helpful, and how the character transforms through the journey… I think it’s really smart. It all blends together very well. It’s a meaningful experience in the end.

The way you play it reinforces its themes beautifully.

I love it as an example, because it’s very much a video game proper. It’s a platformer. On the surface, it would seem too traditional to be interesting… You would think that platformers are so done-to-death that they can’t be new anymore, but the way this format was treated (or understood by the developers) turned it into something very compelling.

There’s not much in terms of obvious experimentation. It takes these individual components and experiments with them within the bounds of the genre.

So, to make something interesting, it’s not like you need to come up with an experimental game that completely re-invents the wheel as something “never seen before”. You can also experiment with very established genre conventions or expectations to do that.

It’s also the little ways that end up making a compelling whole.

Celeste is an interesting one to contrast against a game like Yume Nikki.

Yume Nikki is a game that lets you explore dreams.

It highlights the internal world of the character you play. Nothing is said during the game. Everything is implied. You put together what is happening while you play it, and this gives you a chance to read a lot into it.

I think it’s an incredible accomplishment to make something that communicates so much without a single word.

The game is unique because it has no dialogue, combat, or obvious plot.

Story is implied, and assumed by the player. This inspires a lot of curiosity while playing it.

The metaphor of the dream spaces that you are in, as well as the game not having a strict “voice” (like obvious narrative, and words) makes it a very personal experience. You feel like you are exploring the game with the game.

Playing it opens you up to all these fantastic worlds. It has a lot of dimension without ever being explicit about what it’s about.

I found playing it to be a very liberating experience. It kind of highlighted to me how too much heavy handed story, and explicit direction in a game can make the experience patronizing. Players are curious. They are smart. They can figure it out. Story can be communicated through so many other means (like just the nature of the environment, or the interaction, or mechanics…) it doesn’t have to be constrained to just words and text.

I think Yume Nikki is a notable example when discussing good storytelling in games.

It gives a lot of agency to you as the player. You have to take the time to understand it. It gives you the ability to come to your own conclusions about it. The metaphor of the spaces and interaction make this possible.

I think that games are intrinsically surrealist experiences.

As the video above illustrates…

I think is a really funny example of a game series that kind of “explains” bugs just by nature of it’s story world.

Assassins’ Creed’s premise is that the player is in a simulation (the animus) and playing through memories of an ancestor. The premise is that this is all a “simulation”… So if you find bugs in it that break the immersion (there are lots!) it kind of still makes sense.

I love that about it. Coming from a game design perspective, it’s both brilliant and defeatist.

The more a game tries to be “real” the more you have these issues of being randomly broken out of the immersion, or requiring a ton of suspension of disbelief to see beyond quirky bugs.

If you lean into the surrealism, you have this space that you create where your art “being a video game” makes sense.

Nothing like it can exist. You embrace the fact that games are inherently weird and their systems are prone to breaking.

I think it’s interesting when you take story as the core thing where everything exists surrounding that.

Story is more than a justification for playing a game. It’s part of this entire whole that a game ends up being.

You have that with interactive fiction, but I feel like that genre is fairly constrained by itself. For example, visual novels have a very established format now.

I think it’s inspiring to look at how these genres started, and what types of vision for the medium they evolved out of.

Text adventures are one of the oldest types of computer games.

I grew up playing games like Zork. I think these are worth looking back on to understand how storytelling evolved with games.

Non-linear storytelling is older than video games. For example, see Gamebooks, where the book is read in a non-linear fashion and the reader is given choices at different points in the text.

At that time, I remember how much the concept of telling a story in this format was being explored.

There was this thrill of it all being so new that you likely never experienced anything like this before. The imagination driving this vision behind what it could become seemed endless.

I think the restrictions here helped, because writing was so much at the forefront.

Today all this is fairly established, and these things are viewed as their own genres… All with better graphics.

Still there is something special about stripping these things down to their bare components.

What made it exciting? What did people hope it would become?

To me, these concepts are why it’s important to push yourself to prototype your work in something that is stripped down, where you really have to focus on the basic core of what you are creating.

As game designers, I think we paint ourselves in a corner when we rely too much on that One Tool that does all the hard work for us (like Unreal, or Unity, or the endless plugins for both…). You end up making something that’s too built from templates. You never really get to explore the basic concept of what this thing is outside of all these existing definitions.

Think about novelty, uniqueness, your very own approach to telling a story or what your core mechanic represents.

* A short history of Flash & the forgotten Flash Website movement (when websites were “the new emerging artform”)

* The Flash game movement, my early Flash work, and how Flash games informed what we have in indie games today…

The early Flash website movement very much embodied a lot of what I’m talking about. For further context I did more writing about that, and the links are in this slide…

Things like a website, or just a UI, were more than some utilitarian two-dimensional thing that you pass over.

Websites were viewed as art, and a type of creative expression. At the time people were actually talking about websites as a “new emergent artform”. That’s a strong contrast to what we have today, and it should underline how important art and experimentation is.

A web presence was treated like an environment that held space for a story. It was an experience!

Even something as simple as a portfolio website was story-rich. It had to be if you wanted to be noticed.

I’ll show you a few examples of what I mean…

* The 2 Advanced collection of websites. They where once one of the most imitated styles in web design. Notice how every single element has it’s own motion and kind of “life” applied to it. Each component transitions, reacts, and responds seamlessly as part of the whole. It’s meticulous.

The interesting thing to point out is the science fiction vibe it gives off. I’d like to argue that it’s a good example of “story” in the context of UI design because there’s an underlying theme of fiction to everything. This makes it compelling to look at as well as explore.

* Tokyoplastic was a very early cult website that had a huge influence. Everything is an animation. You randomly click on things… one thing leads to the other with very little context of where you are, or knowledge of what leads to what. The experience is still compelling by today’s standards, because it’s so mysterious. It also presents a strong “theme” (story) to the space it has created.

* The Tonic Group flash website is another example of a compelling layout, with vague navigation that plays out as more of an experience. A series of spaces linked together through interaction, the spaces seem to tie together as a type of “story”, alluding to a journey through digital space.

It’s worth pointing out in many of these how there’s not any obvious way to know what you are clicking on… which in principle is bad usability, but understanding where you are going , or knowing what you were clicking on wasn’t the point.

The point was to create an audiovisual experience. The journey was the point.

This “journey” was a core philosophy of the early internet.

Websites were a journey. You can see remnants of that ideology in some of the language that’s still left over like “surfing” the web, or the very old term “internet superhighway”… you went places, and discovered things.

* There are more in the WebDesignMuseum collection. It’s a noteworthy set of examples that illustrate how theming and story made these digital spaces compelling environments to explore. I see these as an “evolution” of the Geocities era, where people made loud colorful personal “spaces” that illustrated their personalities. These (Flash sites) where polished spaces that served as portfolios, or other spaces of personal expression, with the website being a way to communicate identity. Each space was a different “world” that you could explore. These Flash websites took that type of “early internet spirit” further by creating intricate and animated digital worlds. Websites where considered art during that time. Each website was a space to be unique.

Link: https://www.webdesignmuseum.org/flash-websites

I think it’s really important to highlight that the early web movement was so unique (and as a result influential) because this was all so new.

The rules were not established. The “best practices” and standards not invented yet.

There were no templates for this stuff. It grew from the exploration of a medium.

Games still carry a lot of this type of energy, creative curiosity, or vision.

You can see with most of my examples here, how much story informs purpose. It inspires curiosity.

All that said, if we look past established rules and expectations, that’s what is exciting about video games. We are in no way done inventing ways to deliver good writing in interesting ways, or designing these beautiful mechanics and systems that make a player feel something.

A game is greater than the sum of its parts, and you have to consider all this holistically.

We have this huge space to explore in terms of what it means to bring literature to life.

Literature is not linear. It’s a space that you can exist in, and the way you layer all these different components (from mechanic, sound, space, text) as ways of conveying a story, is a beautiful wheel to keep re-inventing.

You HAVE to keep re-inventing it. Standards kill evolution.

For example, In my own work I have two recent projects that I think turned out fairly beautiful.

The first is A Butterfly…

In A Butterfly, you have this main world and you explore that to find pieces of a poem that describe the metaphor for how you exist in that world.

Then you have these other pieces that are conveyed through Bitsy, Decker, or Pocket Platformer games that you can find. These describe the world in a literal sense. They are the fiction of the space, and less about metaphor.

You play both stories at the same time, experiencing the poem, and the fiction, and then both meet at the end.

The poem is about metamorphosis (overcoming your circumstance), and the story is about letting go of form (as a metaphor for personal death).

So these two pieces of literature happen at the same time, and tie together at the end of the experience.

It’s a short experience, made to be an interactive poem.

A Butterfly was an early attempt for me to (as seamlessly as possible) merge small game engines together into Unreal to give dimension to the narrative.

Which brings me to my big point of this talk blog post…

Why merge game engines?

Links in this slide…

* https://www.wareware.rip/

* https://thecatamites.itch.io/magic-wand

* https://wwwobble.org/

You can benefit a lot from having a general understanding of the smaller indie game engines space, and niche tools that exist out there.

Whatever you can think of, there is likely a tool that (in a very specialized sense) supports that.

Recent examples are ones like ware-ware.

The developers cited thecatamite’s Magic Wand as one of the inspirations for the engine.

You can definitely see what type of game and aesthetic they’re aiming to enable.

I think this is an interesting case, because the type of game this enables is already so incredibly niche.

There are other tools that get even more specific than this.

Another recent development is Wobble Web. A tool similar to mmm.page or Downpour, Wobble Web empowers people to create and share small websites, directly from your phone. It’s a graphics editor and coding environment.

I mention these because they’re new initiatives, and you can see how incredibly specific either of them are.

They are very specialized toward a certain use case or genre.

Small game engines like Bitsy, Pico-8, or any others of similar scope make prototyping much easier than if you would prototype in the large tool you use.

For example, prototype basic environment and dialogue interaction in Bitsy. Prototype gameplay in Pico-8. Twine is wonderful for quickly prototyping dialogue trees…

You can test or iterate a lot faster because you’re not worried about getting basic weird functionality to work in your big engine. Fighting with your engine kills ideas (and there’s always some weird quirky niche bug or issue you run into that can take days) .

It’s harder to focus on testing ideas in these bigger more complicated environments.

If you test ideas in a small engine, where your intention is to throw the prototype away to move onto building the project in the main tool, then you give yourself space to grow, without falling into bad habits… there’s often the temptation to keep the prototype and build onto that, which causes issues later.

It saves time, energy, and keeps you from building onto something that should be moved on from. Prototypes are throwaway. You sketch out interaction, and functionality, then move on from that into your larger project to refine the concept.

Prototyping in small tools encourages you to jam out a lot of different concepts, without being tempted to polish or fixate on details (they’re small tools, which are already constrained).

If you have an understanding of engines out there, you can pick ones that best support your specific basic idea, rather than (again) getting stuck struggling to get the same core functionality to work in the bigger engine.

In my opinion, Pico-8 is probably the best prototyping tool that exists.

It’s always worth mentioning that Celeste started as a Pico-8 gamejam project.

Having little tools helps test ideas!

Understanding the tools ecosystem also means that you are supporting indie toolmakers.

I think this space is novel because each engine will be good at something specific. With that specific thing comes advantages. If I was to build something like Twine in Unreal, it would take me a lot longer to get to the point where I’m ready to flesh out my actual idea so I can explore it.

If I prototype the same in Twine first, I can move on to Unreal when I’m confident that I have a solid approach. It’s so important to be able to jam out ideas fast.

So, for context of why I think this is exciting for storytelling in games…

I’ll show you my unreleased game that I’m working on right now:

The story here is structured with various small game engines being embedded into eachother (they’re all HTML based, so things like iframe)… Bitsy is embedded in Twine, and all that is running in Unreal.

Because they’re HTML they can be made to look like anything with CSS, so there’s really no consistency issue with aesthetics.

Understanding how these tools work means I can combine them seamlessly to create this layered dimension in the story that I’m telling.

You interact with this Twine story, and inside that you have Bitsy 3D (or other engines) that act like “illustrations” to what the story is talking about. If you interact with these interactive illustrations you get a closer look into the narrative of the game world. You can go as deep as you want with this. You experience the story in a more traditional way, or you fall down these rabbit holes that elaborate in whatever moment in time you are exploring.

Basically I’m using the specific strengths of these small tools to my advantage by merging them with Unreal.

These smaller tools made exploring these ideas, as well as fleshing out the functionality so much easier than if I was working just in Unreal.

If I didn’t have these, I would need to have a clear idea of what I want, so I wouldn’t really be able to experiment to see what would work or not work…

These tools made layering that type of complex story possible.

I could go much further with this concept, like if I wanted it to evolve (now that I know what I want, and I’m guided by some good concepts), I would port all this functionality into Unreal, and make all that work even more cohesively with the core game that I have.

For example, these little interactive-illustration windows, could be actual spaces in Unreal that you explore and play in, all contained in this interesting text wrapper, and you can keep going deeper and deeper. Basically windowing interaction even more.

For now I’m using all this to structure the story in a compelling non linear way.

I think all this is exciting because when we talk about game story we often use words like “non linear”. When we say that, we think of branching options, and branching outcomes. We don’t really consider that it can get so much more complex than that.

Story can be this dimensional thing.

You could have layered AND branching. Where a branch leads somewhere, then you have this embedded thing, with it’s own branches too, and you can keep falling down these complicated rabbit holes…

Planning all that structure is possible with understanding these smaller tools. If you understand tools like Bitsy, Twine, Decker… Then you can combine their functionality together to explore how you want to structure a complex story.

It saves so much time.

Letting players explore a story, rather than carefully guiding them through it, is always much more compelling. We play games because we like to experience them and discover their worlds. It’s special when the fiction is built in a way that empowers players to do that on their own terms.

We can explore concepts beyond these established ways of storytelling in games.

You can get as weird, complex, layered, and dimensional as you want.