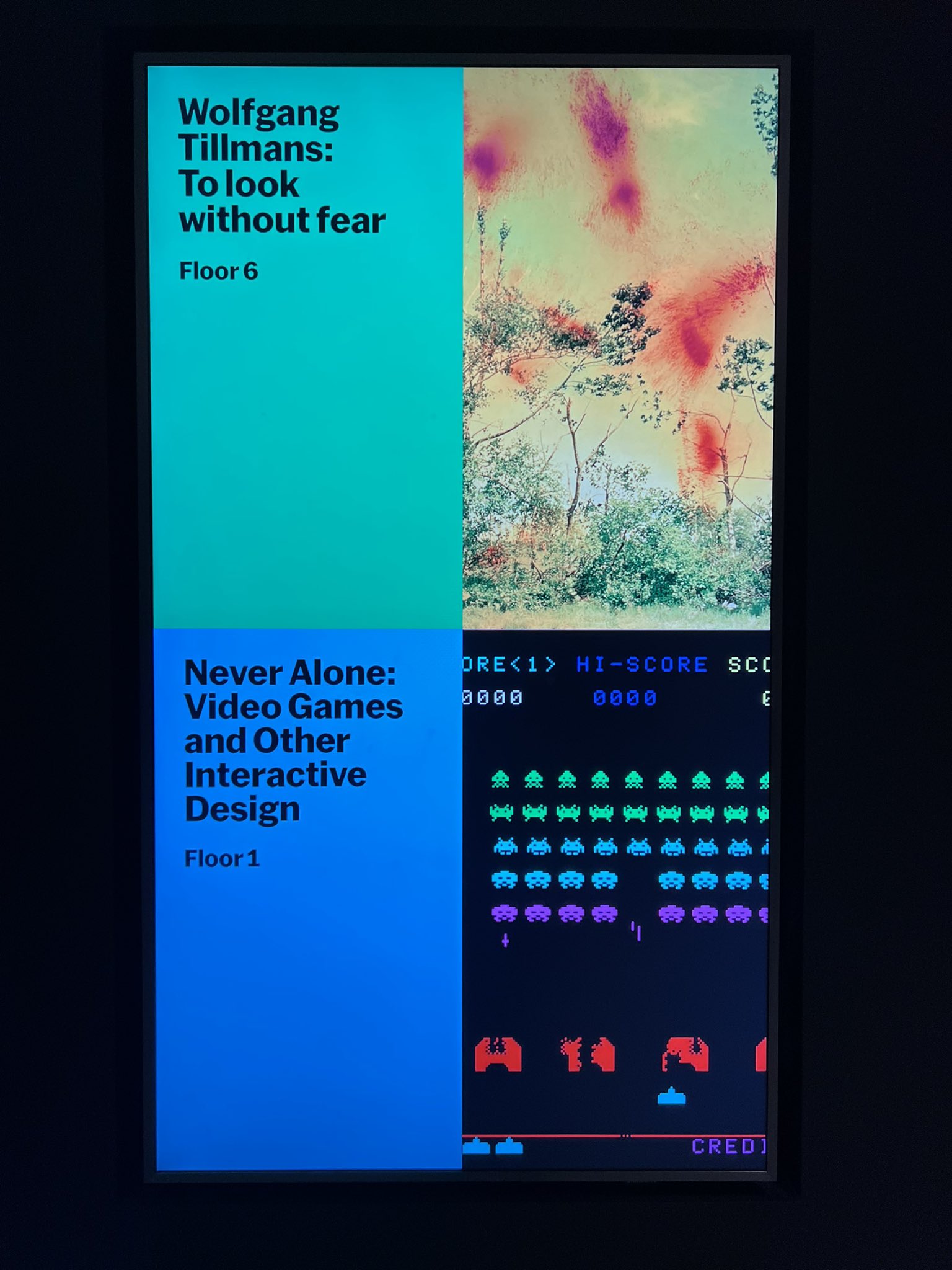

I just came back from visiting New York City to attend the opening for MoMA’s newest exhibit all about video games, interactive art, and the “@” sign.

The exhibit is also accompanied by a book in the MoMA Design Store.

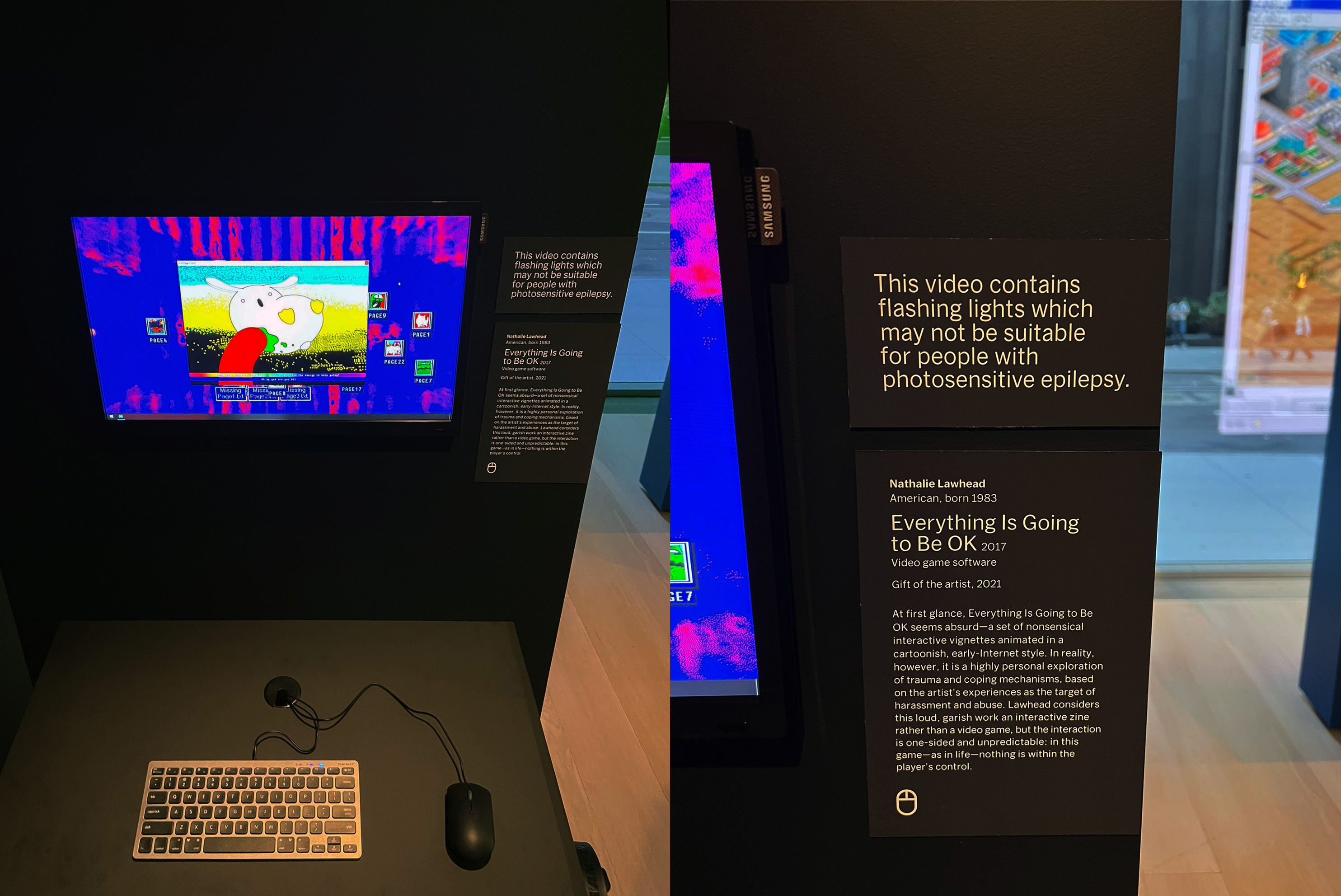

In case you haven’t heard, “Everything is going to be OK” was one of the games that the museum acquired!

MoMA’s journey into acquiring (and effectively preserving) video games has been an effort they announced back in 2012. This was met with much controversy in the art space, as most notably captured in the Guardian article titled “Sorry MoMA, video games are not art”.

Some things don’t age well. This is one of those things.

As anyone that follows me or my work knows, I’m far too familiar with this type of response.

If games are art then we have to embrace the idea that they don't have to be fun. Art is not always fun. It covers a wide spectrum of emotions, and concepts. 1/6

— Nathalie Lawhead (@alienmelon) November 26, 2017

The hazards of classifying your art as a “game” means that it will be held back by the baggage of that label. Forever doomed to be stuck in a limo of not being “fun” enough to qualify as a “game” (as gamers will yell at you for), and shunned out of serious art discussions because it’s “just a game”.

For myself, navigating the classification of “game” has been a difficult journey. The reception to “Everything is going to be OK” from the gamer space can best be captured in my “Day of the Devs” post, where I talked about how people that played it did so imitating famous streamer’s reactions to such games (shouting things like “haha what the fuck is this, drugs?”)… in a mock performance sort of way.

“My point is that wow Streamers and Youtubers have created a steadily growing culture where it’s kosher and a fun pastime to laugh at these types of games.”

–my post “Day of the Devs” observations about how people view/treat art games and their creators

Ironically enough, Venturebeat republished the post (under a more clickbait headline, admitedly…) which lead to more harassment. Sometimes you just can’t catch a break.

YouTube culture is turning kids against art games https://t.co/OV9axqFCnQ by @alienmelon

— VentureBeat (@VentureBeat) November 22, 2017

Most of the surviving comments to this tweet are a great example that encapsulate the atmosphere of the space at the time.

I think it’s interesting to highlight older comments like “If you didn’t want to be harassed you should have made a fun game” that served as supposed justification. These, I felt, further illustrated the issues of the space.

This type of friction followed the entire development of “Everything is going to be OK”, and even made its way into the game. In “Everything is going to be OK” you can find an audio player that plays “Streamer commentary”. You can choose from a large selection of “Lol what the fuck is this??” “Haha drugs!?” comments that will scream over you as you play.

“Everything is going to be OK” was a polarizing project to work on because, on the one hand, I would have people telling me that this game saved their life and made a big difference for them (so many, I can’t even count anymore)… on the other hand I would get comments from angry people harassing me to no end for a game that is essentially about surviving abuse.

This type of mentality has followed me through games ever since I started with my initial “interactive art” project, BlueSuburbia. I did a lot of public speaking on this type of culture.

I make it a point to bring all this up because I think the way MoMA has approached this signifies a critical turning point. Coming from snarky takes on the Guardian along the lines of “No Picasso … Pac-Man will go on show at New York’s MoMA in 2013″… to now having these games showcased in the same building where you will happily stumble into a room proudly showing Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, or Pollocks spatters, says a lot about how the artists have won.

I think it’s worth pointing out that much of what MoMA has in their collection, at some point, also received the same friction.

When early impressionist paintings were first put on display visitors were visibly angry and some even attended these exhibits specifically to laugh at them. It’s an old story that also repeats with photography.

I’m glad that MoMA does not give up.

“Even in its first decades, MoMA engendered debate and controversy. Much of the criticism came from journalists and concerned the nature and validity of modernism, but artists and staff sometimes joined the fray.”

–Messing With MoMA: Critical Interventions at the Museum of Modern Art, 1939–Now

I asked Paul Galloway if the initial negative reception to including games made them hesitant about what they were doing and he said that, to them, it was like water off a duck’s back. Then he listed some past controversies, such as when they first started acquiring photography.

Good art is controversial.

Celebrating art that is controversial, as in the controversial part of it being critical to the relevance of the art, is something that I grew up with (it was a pinnacle thing for art to do) but eventually I learned to be ashamed of this. I can’t help being anything else, but still, it is hard to be.

Existing in a commercial space means feeling a constant pressure to “please the audience”. It was tremendous to be reminded of that older value.

The commercial nature of the game industry places a preference on pleasing the player, optimizing for entertainment, selling… As an artist, to exist in a space so commercial is a constant struggle of assertion.

Not only do artists have to deal with such friction, but the lack of preservation for digital work makes existing here a special type of precarious.

Digital art is always dying. That is my stance.

To make it is to accept that it will be destroyed too soon. The constant march toward technological “progress” makes it a constantly shifting, dying, renewing, and deprecating field. I spent almost seven years building BlueSuburbia, just to have it completely dissolved. It still technically exists, but nobody can access it anymore. A good addition to this discussion is this ArsTechnica article pointing out “Over 90 percent of pre-2000 gaming source code may already be gone.”

This is a constantly dying and shifting field.

All that said, what MoMA is doing is no small feat. I have to admire how they are just diving right in, ready to make the mistakes, ready to pave that way… There’s a difference between just putting an .exe up on the Internet Archive… and actually making sure that you have a permanent way of keeping said .exe accessible. To ensure that it will forever run. Emulators only go so far, or last so long.

I’ll point out that, even with all the work done on them, Flash Emulators still don’t emulate all of Flash. Many games remain broken.

MoMA is coming from the much more difficult approach of making sure that these things are actually preserved, true to the term.

I’m told that digital work is the most difficult and fragile thing they presently have. Universities will teach painting conservation. There are degrees for this. “Saving the paintings” is a profession. There is no established rule book for digital art conservation.

Everyone doing it is kind of figuring it out as they go. The French National Library in Paris has their own initiative. BnF has one of the largest collections of it’s kind, with around 20,000 video game objects preserved (source).

I know this because the year I was invited to speak at IndieCade Europe the event was hosted at the BnF. The Library invited all the devs in the showcase to PLEASE submit their games to the collection so they can be preserved. BnF was sincere about this!

–PRESERVING GAMES: THE IMPORTANCE OF LEGAL DEPOSIT – a talk by DAVID BENOIST at INDIECADE EUROPE 2019

I could go on and on listing all the initiatives that exist, from the many institutions who see the value in creating a true history of digital art. It would probably end up being a book. The Rhizome ArtBase also exists and there is the Electronic Literature Collection…

Many initiatives only go so far as offering the executable (any form of the final built and published file), but often do not ensure that there is a permanent way of running said executable (published file) in the event that a platform has completely changed. Formats become obsolete all the time. What then? Not everything is emulated.

All this is part of an ongoing critical discussion on “how do you even do this?”

Digital work is fragile. It was not meant to last long. Just the act of preservation means working against the grain fundamental to its digital nature.

What MoMA has set out to do is a unique and difficult undertaking. Making a curation is one thing. Every game festival does this. Making sure that said curation can live on past the life expectancy of whatever platform it was built for is an effort of presently unknown scale. However difficult, they are diving right in.

Entering the exhibit, it would be easy to think that maybe they are not “serious” because (on the outset) it looks small, but just for ten games they have an entire crew of people that worked to make sure they really are represented, preserved, secure (running something on a computer that the museum goer can’t just “break” or “close”)… When I asked about it, just making sure that all these very different games on all these very different devices all run properly (unattended) is a hurdle in itself.

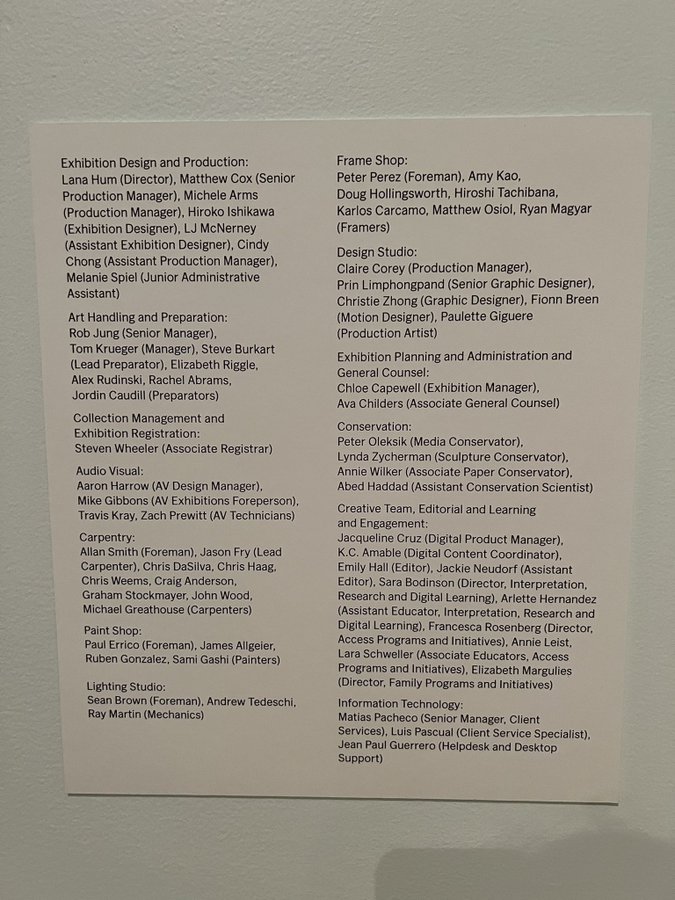

Thanks to the staff that made this possible!

I’ll also point out that MoMA is a unionized museum. I learned that from talking to them.

All that said… none of this is small.

The way games are treated and perceived just got much more serious. To me, this signifies a change in overall perception (for many people, not just the art world).

I believe this is a light at the end of the tunnel toward a better future for this type of art.

Weird art wins in the end!